Central Theorists:

- Jim Cummins

Educational Acronyms of Note:

- BICS (Basic Interpersonal Communication Skills)

- In a nutshell, the day-to-day language used to navigate normal everyday conversations and situations.

- CALP (Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency)

- Essentially any specialized jargon for a topic of study or discussion. They can include something in the classroom (such as math or science) or related to interest (such as skateboard or Magic the Gathering terminology)

Abstract:

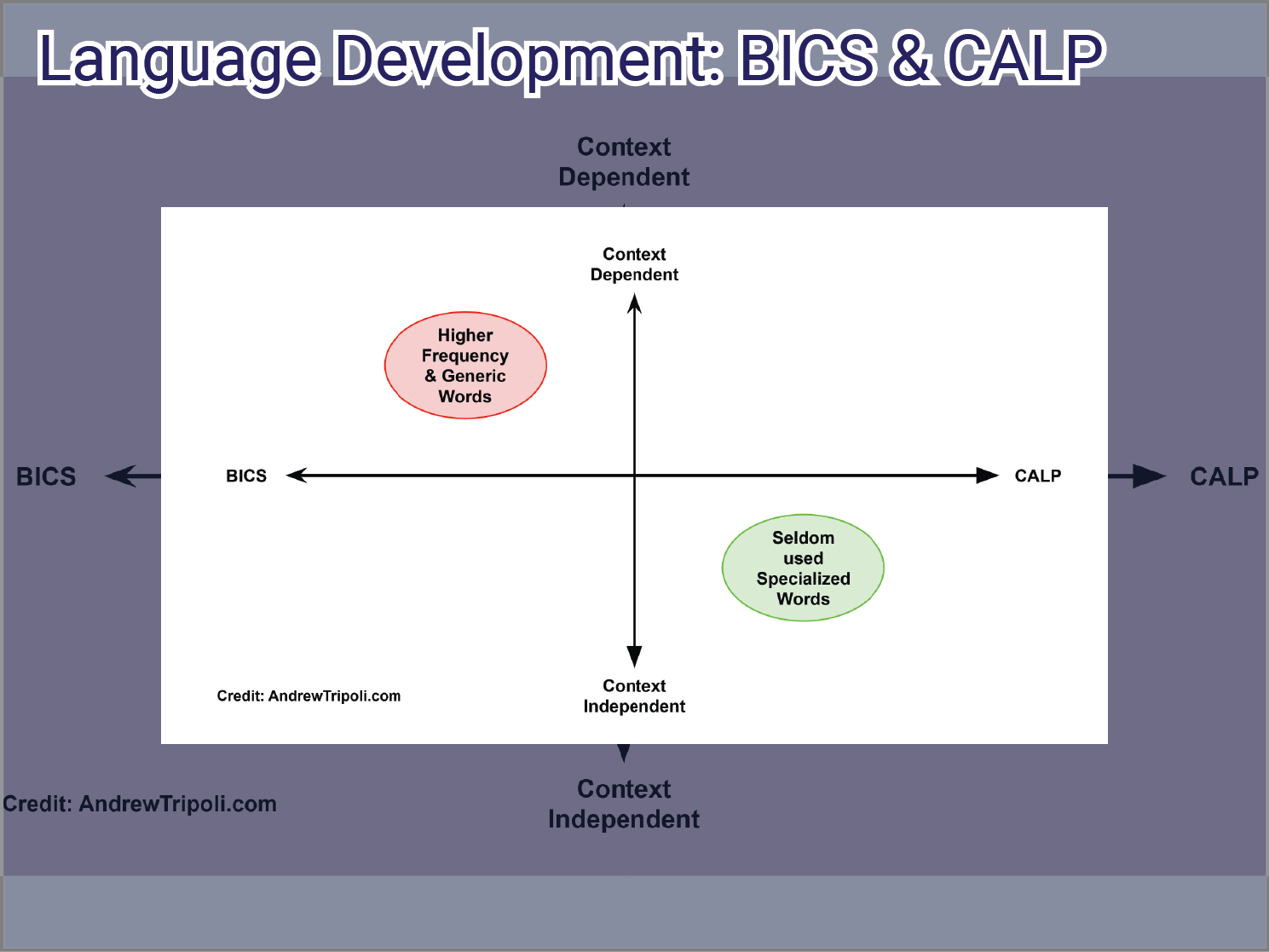

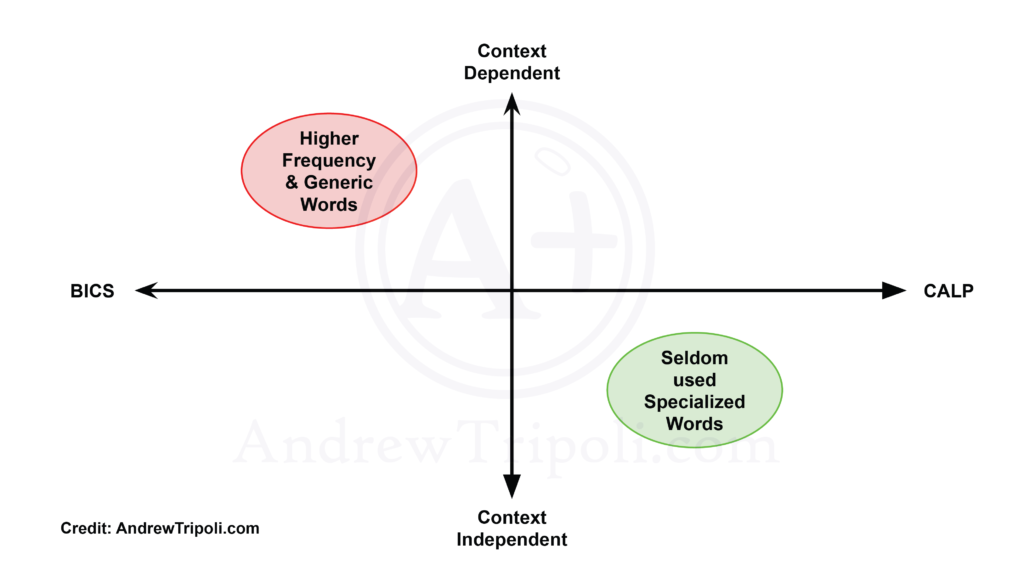

Hello wonderful readers. As always let’s dive into another fun and fascinating teaching philosophy and how we can use it for our personal and classroom growth. Today’s concept is how language develops across two interconnected dimensions. One dimension focuses on the difference between everyday language (BICS) & specialized vocabulary (CALP). Said another way, this dimension is focused on how much basic or advanced vocabulary is needed to communicate effectively. While student growth between these dimensions is considered slowly developed (~5-7 years), We can use the general shape and concept to develop stronger lesson and unit plans.

Concept Overview:

The figure above gives us a rough shape of things. We were just introduced to one dimension (BICS & CALP), but there is a second dimension focusing on context. Context is situational awareness and positionality. For example, if one were to say “bank” one may think of the side of a river or a place to deposit money. By itself this word is context independent. If I were to give a bit more, such as saying “I need to go to the bank for a loan.” or “I want to catch frogs down by the river bank.” One now has a much clearer idea of what I am discussing.

Context, and the lack of it, becomes more important when one thinks about specialized vocabulary or jargon. For example “season” within sports could be a series of games played within a period of time, typically with a winner, or it could mean to add flavor with herbs and spices within cooking. An even more specialized example is “Jib”. In boating one would mean the shape of a front sail. In engineering one might mean a heavy lifting tool such as a crane. Lastly, In conversational speech, one might use the idiom “the cut of one’s jib” to mean their general demeanor or attitude. Note that once we introduce an idiom the context goes away. A person is not a ship or heavy lifting tool, nor is the speaker making a comment on someone owning one.

Since the context dimension asks how much situational awareness or context is needed to understand what is being discussed, we might recontextualise the dimension as focused on how familiar the situation & topic of conversation is for the language learner.

Now that we’ve gone over the general shape of things let’s go over their combined relationships. This explanation is rather basic. In general, language learners learn and integrate language from the top left of the figure to the bottom right. Said another way, learners first build a base of word awareness and its more generic context and then integrate more unique contexts and associations before being able to apply the word to nontraditional, unique, or context independent situations.

Let’s return to our season example. A typical learning process might start with weather & seasons. The learner realizes there are four seasons: winter, spring, summer, and fall. From here they might come in contact with sports where they use the previous context (change in weather & features over a year) to help them understand sport usage (change in sport & winners over a year). They also come in contact with cooking seasoning (change in flavor & quality based on cooking strategy such as time). With this context they then start to apply it to less formal or established patterns in their own life. For example in teaching I might say “final grade season” meaning the time toward the end of a semester when grades are given, student comments are written, and teachers start to finalize unit plans for the next semester.

If this process seems complex or lengthy one would be correct. Most estimations of this process for language learning are around 5 to 7 years. Fortunately for us and how we can use this in the classroom this is not the case for individual words and concepts and we can dive into how to specifically use this below.

Practical Application

This section hopes to answer the age-old professional development question “so what?” “Why should I care?” &/or “How can I use this in my classroom?” In short, recognizing this pattern of language development and growth allows educators to develop much stronger lessons in a couple key ways.

First, it gives them a reflection tool to check in with their students. I can’t tell you how many lessons I’ve observed or taught and gone “what happened? This content is super easy.” Only to realize I had jumped too far into a context that was too specialized or unfamiliar given the student level, background, or interest. It’s a result of a classic thought process we are all guilty of from time to time. “If it’s easy/familiar to me, it must be easy/familiar to everyone.” Or “I learned this when I was (insert statement showing my age) so this is clearly appropriate here and now.” The additional reflection tweak to make is “what was our own context & is/was it similar to our students?” The answer is often, and sometimes frustratingly, “no!”

Second, it gives us a framework to structure our lessons and/or units when we introduce new concepts. We can use the figure above to introduce & precheck ideas with conversational and generic contexts and guide them along to more specialized and non-contextualized situations. This can be incredibly useful in non-English subject classrooms where English as a Second or Other Language (ESOL) learners struggle. The situational transitions can really help improve learning outcomes.

Thirdly, it helps to decouple conceptual learning and vocabulary. For example, think of a time you had a memory lapse (sometimes called a “brain fart” or “senior moment” or “drew a blank”). What did you do? Likely you described and defined the term letting the definition stand in for the missed vocab word. Further, I’d suspect the other person in the conversation did not think you had no idea what you were talking about; and yet, this is often the case with language growth and development. “You didn’t know the vocab word, so you must also not know the concept behind it.” Giving students the chance to replace specialized vocabulary with more generic language can therefore be empowering for language learning students especially in non-English subjects which focus on specific terminology.

Lastly, it gives us an idea for summative assessment. An educator can set a goal and generate an assessment that speaks to that considered outcome. Thinking on how contextual, formal, & specific our outcome is a great way to add scaffolding and differentiation considerations to our planning.

Now I’m not just going to leave this topic here. Let’s put this into action with a quick unit lesson development process we can use. Since I made a fuss about non-English subjects, let’s develop an 6th-8th grade science unit on Ecology. I’m using the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). These can be found here if you’d like to check my work.

Before we begin, as an exercise, I would like you to consider how a traditional classroom may teach this subject. That way we might develop a contrast that can help us in a minute.

Finished? If so, great! If not, take a moment before reading on.

In a traditional classroom the teacher took out the book and taught each skill independently. Separating food webs, conservation efforts, cell biology, respiration, energy cycling, and living vs. nonliving factors. That’s the curriculum and what the book says. It would typically end in an exam with each question focusing on some tiny chunk of understanding. This again separates out each concept to a particular question limiting connections and contexts between unit ideas.

In comparison let’s look at the following protocol with our consideration of BICS, CALP, and context.

Step 1: Scan Curriculum for Core Ideas/Concepts

- Photosynthesis & energy cycling through an ecosystem

- Photosynthesis & chemical reactions related to chlorophyll

- Consider the role of living and non-living elements of an ecosystem for energy/matter cycling

- Develop a model for energy and matter cycling

- “10% rule”

- Producer

- Consumer (primary, secondary, tertiary, apex)

- Scavenger

- Decomposer

- Closed and open energy & matter systems

- MS-LS2-4 “Construct an argument supported by empirical evidence that changes to physical or biological components of an ecosystem affect populations.”

Step 2: Simplify Key Concepts Around Related Contexts

- Create a developed food web/ecosystem including biotic and abiotic factors.

- Develop and understanding of the the chemical reactions/processes related to photosynthesis

- Consider how the limitations of abiotic & renewable factors affect biotic factors within an ecosystem.

Step 3: Link Related Contexts to Provide a Final Assessment

- Students will create an ecosystem model that considers the biotic and abiotic needs within a system to support a single apex predator.

Step 4: Check Vocabulary List for Directly Relevant Context in Final Assessment

- I could pull many more, but focusing on 5 typically difficult words

- Biodiversity

- Contextualized as students realize the varied levels and variety within an ecosystem to support an apex predator

- Eutrophication – (greek meaning Eu=”good” trop=”nourishment” ication=”process/state of”. Literally meaning “process or state of good nourishment”)

- Contextualized in relation to biodiversity showing how even when things are good if biodiversity is not existent there may be issues.

- Photosynthesis

- Contextualized as students recognize this as a key feature and link adding energy to the ecosystem & a primary touch point where an abiotic factor transitions to a biotic factor

- Trophic level

- Contextualized as students build their ecosystem and discover the connected food chains that directly and indirectly support the apex predator

- Sustainability

- Contextualized through the consideration of the ecological system and to what extent it is open or closed and how the “10% rule” can help systems self-regulate.

Looking above I hope we can see the benefits, but let’s check in with our aims. As a reflection tool it allows us to see what connections and concepts are weaker rather than not getting a vocabulary word right on an exam. Second, there is now a stronger structure as one can continue to add links through their teaching to build upon prior knowledge. Thirdly, as students explain their models one can see the gaps of vocabulary vs gaps in conceptual learning. Hearing “the lion eat 10 deers that eat 100 grasses that use light to eat the sun” definitely isn’t the best English, but does tell us the student learned the concept of the rule of 10% and how photosynthesis plays into this process. Lastly, our unit and structure was focused around our summative model providing a clear goal for students outside of “at the end of this unit we will have a quiz on these ideas”. As we can see this model certainly helped improve our development of the unit.

Thanks for reading If you liked this article feel free to share this wherever you find it most helpful. If you or your organization would like help developing more effective lessons or units or would like to hire me for professional development opportunities feel free to reach out to me at Info@AndrewTripoli.com. You may also find additional related resources on our Teachers Pay Teachers page by searching for Andrew Tripoli.